William Oddie is a regular writer for The Catholic Herald. He also writes for a number of conservative-Catholic journals such as Crisis Magazine: a voice for the faithful Catholic Laity.

In a recent article published in The Catholic Herald, Dr Oddie began what looked to be a review of a new book by Joanna Bogle. However shortly after giving the reader a taste of what Bogle's book holds, and from what I have read by Oddie and Bogle, it looks like a book worth getting, Oddie launches into a a re-hash of many of the old chestnuts that apologists for Pius XII have used for decades. Bogle's book concerns two English Bridgettine sisters who were active in rescuing Jews in Rome during the German occupation (September 1943-June 1944). The story on its own looks to be a compelling one. It doesn't need to be turned into a propaganda item by those who wish to use any story of rescue for political ends. I fear this is what Oddie has tried to do.

The insertion of a lengthy quote from David Dalin and recycling the long-debunked claims of Pinchas Lapide, lends aid to my fear that Oddie is more interested in keeping alive the dying flames of an old argument that most mainstream historians have long since walked away from. The "vilifiers' of Pope Pius XII are not those who disagree with the ahistorical arguments of Dr Oddie and company, but rather the apologists themselves who dabble dangerously close to denialism and a reckless disregard for the truth. It is Oddie and those who believe his version of events who insist on making the arguments for and against Pius XII a litmus test of Catholic orthodoxy. Historians will keep on with the business of history.

Nonetheless, I look forward to reading Joanna Bogle's book.

Here is William Oddie's review:

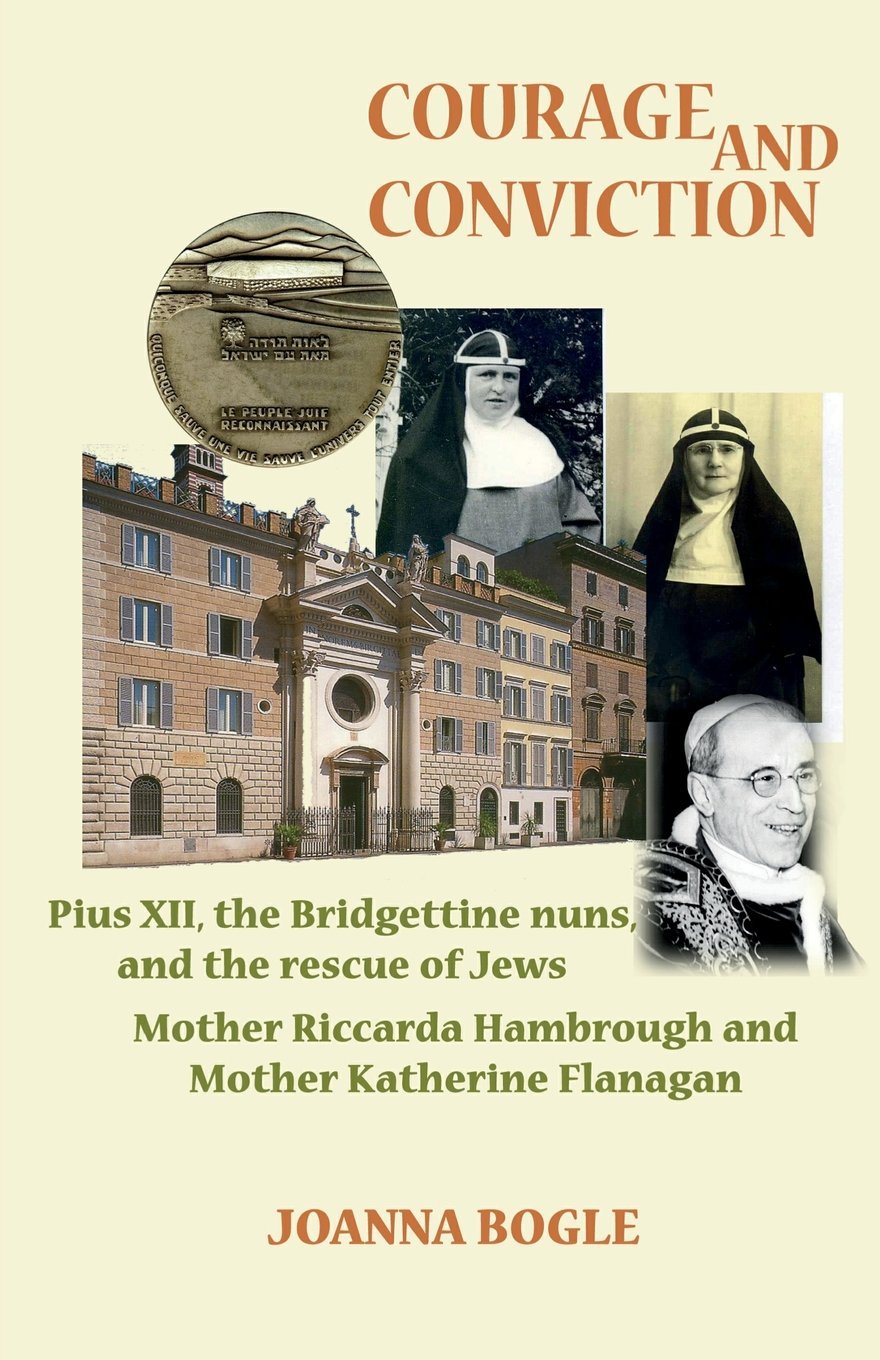

Joanna Bogle has written prolifically and devotedly on a wide variety of subjects, always defending and proclaiming the values of the Catholic Church and aimed at nourishing in her readers the capacity to live the Catholic life; and her writings are undoubtedly an important part of what led recently to her deserved elevation to the rank of Dame of the Order of St Gregory. I have just read another of her books, shortly to be published by Gracewing, which everyone should read when it is published later this month: Courage and Conviction, the story of how two English Bridgettine sisters, Mother Riccarda Hambrough and Mother Katherine Flanagan, sheltered Jews in their convents during the German occupation of Rome. This account is invaluable, as a vivid insight into one small part of the much wider effort by religious houses and other Catholic institutions throughout Rome and the whole of Italy to shelter Jews from the Germans after the fall of Mussolini in 1943.

On the general question of Pius XII’s part in the shelter of Jews throughout Italy, Dame Joanna’s book is a useful guide, especially in the face of the persistent propaganda attempting to show that Pius XII was, to quote a particularly disgusting book title, “Hitler’s Pope”. As she points out, the majority of Italian Jews – some 80 percent – survived the Second World War, during the years when, across Europe 80 per cent of Jews died. She quotes J Lichten’s book [sic] A Question of Moral Judgement: Pius XII and the Jews,(1963) one among many accounts of what until recently was widely known and accepted by everyone (especially by leading Jews like Golda Meir), that “The Pope sent out the order that religious buildings were to give refuge to Jews, even at the price of great personal sacrifice on the part of their occupants; he released monasteries and convents from the cloister rule forbidding entry into these religious houses to all but a few specified outsiders, so that they could be used as hiding places. Thousands of Jews – the figures run from 4,000 to 7,000 – were hidden, fed, clothed, and bedded in the 180 known places of refuge in Vatican City, churches and basilicas, Church administrative buildings, and parish houses. Unknown numbers of Jews were sheltered in Castel Gandolfo, the site of the Pope’s summer residence [according to Rabbi David Dalin, at least 3,000 found refuge there], private homes, hospitals, and nursing institutions; and the Pope took personal responsibility for the care of the children of Jews deported from Italy.”

As Dame Joanna points out, the scale of the rescue operation was huge. In the City of Rome itself 155 convents and monasteries sheltered around 5,000 Jews. Sixty Jews lived for nine months at the Gregorian University, and a considerable number in the cellar of the Pontifical biblical institute. One could go on at wearying length.

The story of the English Bridgettines, Mother Riccarda Hambrough and Mother Katherine Flanagan, is one small and typically courageous part of the huge operation that Pius set under way. What emerges vividly is not only the vital part played by the Pope himself; but the indispensable part played by the faith and courage of so many individual Catholics who obeyed his call.

Mother Riccarda hid about 60 Italian Jews from the Nazis in her Rome convent, the Casa di Santa Brigida. She was baptised at St Mary Magdalene’s, Brighton, at the age of four after her parents converted to the Catholic faith. She was guided towards the Bridgettine Order by Fr Benedict Williamson, who was the parish priest of St Gregory’s Parish, Earlsfield, between 1909 and 1915. Sister Katherine Flanagan, too, was guided by Fr Williamson and also joined the Bridgettine sisters.

What is striking is the way in which, as far as possible, the Sisters made it possible for those they sheltered, not simply to cower in hiding, but to live normal and dignified lives. One refugee remembered that they had asked for refuge, but without saying at first they were Jews. They went to Mass, copying what the Catholics did. They were soon told that “we must live our own beliefs, that we should not feel any need to pretend, and that we must live and pray as Jews”. The same refugee told Dame Joanna last year (this book is not a scissors and paste job), that “I was even able to continue my education: a lady professor, a Jewish lady, came in and gave me lessons. She taught me Latin. We studied Tacitus and I became really engrossed in it. It was particularly important for me because earlier the Jews had been kicked out of all the schools, and I could have missed out on the chance of an education. But because of this tutoring, when the Allies arrived and we were liberated, I hadn’t missed a year of my schooling”.

The present Mother superior of St Birgitta’s, Mother Thekla, who knew Mother Riccarda well, remembers that she was “was truly very beautiful. She was a wonderful person — an angel on the earth. And she was humble—she had this spirit of service, of simply wanting to serve and help people”. This is an inspiring story, simply but powerfully told. “Above all”, remembers Mother Thekla, “[Mother Riccarda] had a profound respect for these Jewish guests. It was important not to let them feel humiliated by their situation—they were vulnerable, and it was crucial to let them know that they were welcome and that the sisters wanted to help them in any way they could.”

By concentrating on the Bridgettines in Rome, Dame Joanna has vividly brought to life a microcosm of what was happening wherever there was German occupation after the fall of Mussolini. Multiply this account by a thousand, and you have some idea of what the Catholic Church in Italy, directly inspired by the Pope himself, believed it had a vocation to accomplish.

By no means all Jewish writers today have uncritically accepted the torrent of anti-Pius propaganda, the contents of which over recent decades have generally been assumed by the secular media (and even by some Catholics) to be well-founded. As Rabbi David Dalin has written in a lengthy and important article, well worth reading carefully and in full, though Pius has had his defenders recently,

…. it is the books vilifying the pope that have received most of the attention, particularly Hitler’s Pope, a widely reviewed volume marketed with the announcement that Pius XII was “the most dangerous churchman in modern history,” without whom “Hitler might never have . . . been able to press forward.” The “silence” of the pope is becoming more and more firmly established as settled opinion in the American media: “Pius XII’s elevation of Catholic self-interest over Catholic conscience was the lowest point in modern Catholic history,” the New York Times remarked, almost in passing, in a review last month of Carroll’s Constantine’s Sword.

Curiously, nearly everyone pressing this line today — from the ex-seminarians John Cornwell and Garry Wills to the ex-priest James Carroll — is a lapsed or angry Catholic. For Jewish leaders of a previous generation, the campaign against Pius XII would have been a source of shock. During and after the war, many well-known Jews – Albert Einstein, Golda Meir, Moshe Sharett, Rabbi Isaac Herzog, and innumerable others —publicly expressed their gratitude to Pius. In his 1967 book Three Popes and the Jews, the diplomat Pinchas Lapide (who served as Israeli consul in Milan and interviewed Italian Holocaust survivors) declared Pius XII “was instrumental in saving at least 700,000, but probably as many as 860,00 Jews from certain death at Nazi hands.”

In the end, that truth will once again become generally accepted. When it is, Joanna Bogle’s important new book will have played its part.

No comments:

Post a Comment

You are welcome to post a comment. Please be respectful and address the issues, not the person. Comments are subject to moderation.